3 Must Know Competitive Advantages In Investing (And Life)

Lessons from The Nomad Letters

If I asked you to name an investor who could turn $1 into $10.21, you would probably say Warren Buffett, Charlie Munger or some other famous investor.

Some of you might say Lynch or Soros or Ben Graham or John (Jack) Bogle.

I’m willing to bet you a dollar that not many of you said Nick Sleep and his partner Qais Zakaria. Together, they ran The Nomad Partnership from 2001 to 2014 with an annualised return of 20.8% before closing their doors in 2014.

Sleep wrote The Nomad Letters to shareholders, which has become essential reading for professional and retail investors alike. It’s easy to see the comparisons and education Sleep derives from people such as Munger and Buffet. The Nomad Partnership was a ‘long’ fund, and they vehemently defended that notion. Drawing on previous founders’ mantra of creating exceptional customer value, that’s exactly how the fund was run from day one until its closure.

Sleep got his education from Edinburgh University, where he studied the ‘odd’ subject of geography:

“At this point, I should probably explain something about my background. I studied Geography at Edinburgh University, Scotland. Geography is a subject that hardly exists in North America. A Harvard Professor once told me that they had a Geography course at Harvard, but it had a reputation for homosexual lecturers and was closed down.”

My wife was a geography teacher, and I couldn’t help but laugh out loud at how ridiculous a statement that was. Sleep seen it from a different angle, though.

“ I am not sure what to make of that particularly, I suspect it is not cause and effect, but at any rate, Geography is a subject with an identity crisis – it is the confluence of geology, physics, chemistry, oceanography, climatology, biology and that is just physical geography. Human geography deals with sociology, psychology, statistics, and economics – so it is the ultimate polymath course. Geography just reached into other subjects and grabbed what it thought it had to have. Indeed, the reason I studied Geography at all was because of this polymathic quality, although I got there through an odd route…”

This sounds like Charlie Mungers seeking foundational knowledge advice to me.

In today’s article, I will discuss Nick Sleep’s 2005 Speech given to the board of The Investment Fund for Foundations in New York City titled: So How Does Zeckhauser Play Bridge?”

“And so, at Edinburgh, we spent a whole year on the philosophy and methodology of what we were doing, and that year opened my eyes. I just loved it. I mean, it really changed my thinking. And I was reading “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance” by Robert Pirsig at the time, and the two just combined to change how I viewed the world. So, I have this tendency to return to the basic questions.”

- Nick Sleep

Sleep starts with trying to find an answer to a question asked about his fund: “What is your competitive advantage in investing?” He draws on an answer from Bill Miller, who was asked that question previously, and states that there are three advantages:

Informational: An advantage would be to know a piece of information that the market or others do not.

Analytical: Given the same information, people can chop it up in several ways, arriving at different conclusions.

Psychological: Biases and behaviours that can impair and damage investors or, if understood, can be used to their advantage.

Number one is mostly illegal, number 2 is a matter of preferential philosophy, and number three is a matter of rationality and judgement. With good analytical principles and an awareness of the perils number three brings, the savvy investor, or indeed professional, can gain an edge in their field simply by observing the environment around them.

In his talk, Sleep gives a great example of how you describe something can affect how you think. Using an example from Wittgenstein in the visual below, tell me what you see:

“Wittgenstein’s point is the description you use, will frame how you think. So, is it a coat hanger or a door wedge? If someone described it to you as a piece of cheese, you would think about it differently than if they had told it was a mountain, or a pyramid that’s fallen over. The point is that perceptions change as descriptions change – and they change independent of the facts.”

Sleep gives an investing example of how advertising and marketing are treated as a debt by accountants rather than an investment. Being a holder of LVMH, the luxury conglomerate, I can understand his frustration. LVMH has just ‘invested/expensed’ a billion-dollar contract with F1. I’m not interested in F1 or luxury brands, to be honest, but it’s not lost on me that some of the most famous sportspeople in the world will be standing on the podium drinking Moet and dressed in TAG Heuer watches and Louis Vuitton bags. I suspect that might be good for business.

Not all costs are bad costs, and when Mr Market (people) is irrational, it offers people like you and me opportunities to load up.

One way The Nomad Partnership got around this accounting shackle was to:

“Do a fair amount of turning numbers around, looking at things no one else looks at, such as share of voice versus share of market, which is a way of assessing advertising spend, we assess customer loyalty, we cover up the name of the company and analyse the business and so on. You have to array the information in such a way as to be able to properly weigh its value, and that is not always the same way the accountants use. And I think we have some analytical advantage in that compared to the crowd. But I like it most when it is combined with the final source of competitive advantage and those are psychological and behavioural.”

Sleep draws on his predecessor Charlie Munger’s infamous “Psychology of Human-Misjudgment” speech and the importance of understanding the cognitive biases and influences that affect our behaviour and decision-making processes. There are, of course, 25 of them, but Sleep goes into detail about 4 in particular.

1. Social Proof/Group Think

“Social Proof/Group psychology. Well, we all know something about the dysfunctionality of group-based decision making, you’ve got one guy leading the debate, he’s the authority figure, he suggests a course of action, everyone anchors off that suggestion, maybe bonus time is looming so no one wants to object. You are all aware that a competitor across the road has just taken the same course of action. And nobody objected. Social Proof. And, of course, it’s a perfect disaster. We all know that social decisions can be suboptimal, but even so, that is how most decisions are made… At least on the boards of public companies and investment firms I know.”

How else do you explain the tech stocks people were buying in 1999 just because everyone else was buying them too?

Sleep offers another example. The Thai cement industry was booming in the 1990s, but Siam Cement had built all the capacity Thailand needed. That didn’t stop Siam City Cement and TPI Polene from going head to head, and as Sleep states, “Combine social proof with envy-jealousy, and financial incentives and boom, there you go.”

2. Availability Bias

We tend to over-weight vivid or easily obtained evidence. Sleep discusses a video Dick Thaler uses, who runs an investment company and teaches behavioural finance at the Chicago School of Business. The video is now infamous for showing us we only see what we want to see. There are three people dressed in white and three dressed in black, and they are to pass a ball to each other whilst moving around. All you have to do is count how many passes there are. Simple, right?

Well, most people fail to see a man dressed as a gorilla walk across the court, beat his chest and walk off. How can that be? How can anyone miss that? We tend to get tunnel vision with the task at hand (count the passes between the white trio and the black-dressed trio) and the overall picture (a gorilla walking on the court, beating his chest and walking off.) It’s frightening to think of all the things we may miss because of this bias!

You can’t take for granted the importance (no matter how obvious it may seem) that looking around you can have. When you have the availability bias, financial incentives, social proof, and envy-jealously tendencies, then forget about the small poof beforehand, you’ve just created an Atomic bomb.

3. Probability-Based Thinking

After reading Charlie Munger’s statement, “The right way to think is the way Zeckhauser plays bridge, it’s just that simple”, Sleep went on a year’s mission to hunt down Zeckhauser and find out exactly how he does just that.

Zeckhauser was a bridge champion in 66 and ran a behavioural Financial course at The Kennedy School of Government at Harvard after being rejected by the Economics Department. Zeckhauser’s split with the economist’s view of the world is their reliance on the rational utility-maximising framework.

The idea that we are all rational beings didn’t sit well with Zeckhauser, Charlie Munger later, and now Sleep. A more, dare I say, ‘rational’ opinion might be that we all have systematic biases in our decision-making processes. There is also the biologist’s view of the world that individuals act in self-interest, make mistakes, learn and evolve. Much like Sleep’s choice of Uni course in Geography, Behavioural Finance takes a pragmatic, multi-disciplinary view of the world and interweaves it with the economist’s rational view of the world. This makes sense:

“After all, how can economics not be behavioural-who is making all the decisions after all?”

- Nick Sleep

If Zeckhauser was thinking like this in the 1960s, Sleep until 2014, and Munger up until his death last year in 2023, why don’t we all think like this? Or, to be more critical, why don’t most investors think like this? I think Sleep knows why:

“Articulating this stuff is easy, internalising it is not.”

- Nick Sleep

“Zeckhauser thinks via decision trees and attaches probabilities to the various branches.” When any facts may change, so do the probabilities. This isn’t a normal way of thinking, and it certainly isn’t intuitive. Investors focus too much on the vivid evidence, not on the opportunity cost of selling stocks that go on to rise 10, 20 or 100-fold.

4. Patience

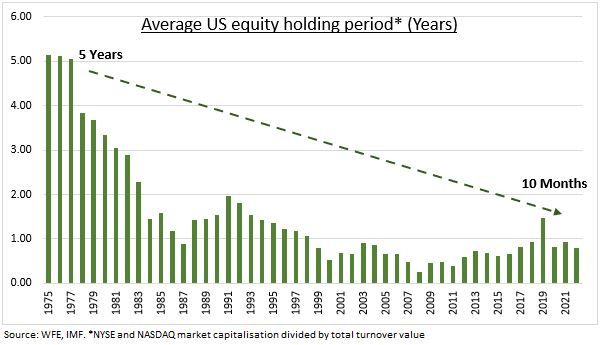

Or lack thereof. When Sleep gave this speech in 2005, the average holding of period of stocks was down to 10 months, down from 5 years in the 1970s. I found this chart on eToro (below) that suggested it’s about the same today!

How can the average holding period of stocks be ten months? After all, isn’t everybody a long-term investor, and didn’t they all subscribe to the philosophy of Buffettism and Mungerism? Well, what people say they do and what people actually do most often are two different things.

The problem, according to Sleep, is the short-term thinking of investment institutions. It’s ultimately a principal-agent problem. If investment institutions and investors alike instead thought from a principal-principal perspective, you naturally would not think short term. You would not trade daily or be interested in quarterly reports, but they do, and they are.

How does this all tie into their performance, then?

“Well let’s go through some of these psychological mis-judgements from an Asian perspective: Well, the Asian emerging markets are Chinese, even in Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines and Malaysia, which have large indigenous populations, the business elite is Chinese. And the Chinese like to gamble – one of our largest investments is in an old Malaysian casino and its chocked with Malaysian Chinese from KL on a weekday, and you should see it at the weekend! - well that does not sound like “patient money” to me. And what have we just learned that patience matters. There is very high social cohesion to Asian societies. That is people think alike, and they think literally. This is true in the west, but I think it is probably more true in the east as eastern societies tend not to celebrate the individual to the extent we do in the west. So social proof and herd mentality may be more acute. That is, contrarian thinking seems to be more rare. And at the trough things are very, very cheap. And they have a principal/agent conflict. That’s Zeckhauser’s other pet subject, the principal agent conflict. So, the foreigners in the region typically think like bullish agents, but that is not how the main shareholders think! the families that control Asian companies view is not the institutional agent capitalism we grow up with in the west (and the self-promotion that goes with that) – its dynastic, confusion capitalism - that is they think like principals. So, in Asia there is this huge dispersion in orientation, between the Chinese gambling mentality of the masses and the tycoons dynastic orientation. The way to bet is not to align yourself with the market patsy, but to think like the tycoons-and our long holding period in that regard-back to patience.”

Above, Sleep beautifully describes the human misjudgements that can lead to poor short-term thinking.

Final Thoughts

This talk from Sleep isn’t as famous as Charlie Munger’s talk on the same subject, but it’s just as important. It’s staggering and confusing to see that the average stock holding period is just ten months, even though so many people subscribe to Buffett and Munger’s long-term thinking. So, where are all the long-term investors?

By understanding your two advantages (analytical & behavioural) and the cognitive biases that can lead us astray and make us impulsive, ignorant, and jealous, we can give ourselves a fair crack at being a good investor or, indeed, professional and person. There are many lessons in Sleeps talk that people outside of investing would do well to learn.

After all, stock picking is the average of your analytical skills, rationality, judgement and patience. I would say these are indeed very good multidisciplinary skills to have.

Until next time,

Karl (The School of Knowledge).

Whenever you’re ready

The School of Knowledge helps entrepreneurs and professionals convert worldly wisdom from books into actionable insights📚💡

Consider joining our growing community of like-minded life-long learners.