An Introduction to Capital Allocation & Why it’s the Most Important Job for any CEO

Understanding why, and how, some business grow and others die

Welcome to The School of Knowledge. A Substack that helps you navigate your personal or professional transition through the hard-won lessons of those who have tried, failed and succeeded—those with skin in the game. Want to go deeper? Paid members get direct support implementing these mental models and frameworks, access to live Q&As, and our private community chat where we discuss real challenges and solutions.

This is the first essay of my second mini-series: An Introduction to Capital Allocation & Why It’s the Most Important Job for Any CEO. Over the coming months, I plan to dive deep into the foundations, principles and frameworks that some of the best capital allocators over the last 100 years have deployed to create excellent businesses for their shareholders and communities—so that you, the CEO or business owner, can make the most informed decisions about how best to use your company’s capital.

Rest assured that I too am a business co-owner of a construction company in the UK, and I will not put pen to paper practices that I wouldn’t use in my own business. After all, this is fundamentally a newsletter for people with skin in the game—those concerned with putting theory into practice.

A note on language: Throughout the series, I will use the terms “CEO” and “business owner” interchangeably. Why? Because the principles of capital allocation apply equally whether you’re running a Fortune 500 company or a private construction business. The main difference is scale and scrutiny—CEOs of public companies must justify their decisions to Wall Street, while private business owners answer to partners or themselves. But the fundamental question remains the same: how do you deploy your company’s cash to create the most value over the long term? You’ll notice most of my examples come from public companies. That’s not because these principles don’t apply to private businesses—it’s simply because public companies must disclose their decisions, giving us a wealth of case studies to learn from. The beauty of studying these CEOs is that their mistakes and successes are documented in detail, allowing us to extract lessons without paying the tuition ourselves.

Let’s get into it.

The Americano you pick up every morning, the car you drive to work, and the clothes on your back are all products of businesses. Now, it doesn’t take a genius to figure that out, but when you stop to think about it, almost everything we interact with is the product of somebody else’s business. They consume our world and give us everything we want, need or desire.

Some people have many businesses, some one, and many none—choosing to work for one instead. They can be run by a single person from their bedroom, or have hundreds of thousands of employees spanning multiple continents. To have a business, you need to have something to sell—like coffee, a Prius or jeans. But it can also be a service such as laundry washing, leasing software or personal training. If you can think of something to sell, and somebody pays you for it—it’s a business.

But how do companies grow—and how is it that some are worth trillions of dollars, and others barely get by? You could argue it’s luck, timing or once-in-a-lifetime ingenuity, and those factors certainly play a role, but I think the real differentiator is something more systematic. Let’s first look at an important distinction between the two types of business owners.

The Two Types of Business Owners

“The business of business is a lot of little decisions every day mixed up with a few big decisions.”

– Tom Murphy

In order to have a successful business, you first need to be confident in three things:

The products or services you sell today will still be the products or services people will pay for tomorrow,

They are of a certain quality, and

That quality is reflected in the price at which you sell the product.

Buying something consumable for pennies and it breaking is not the same as spending thousands of pounds on an Hermès bag and it falling to pieces within three months. Rest assured, the next time the customer wants to overspend on a bag—they’ll be walking over the road to Louis Vuitton.

Good business owners know that they need to run their operations efficiently in order to generate free cash flow. After all, if you don’t have money—you can’t invest it. With that said, you focus exhaustively on this mantra and have your day-to-day operations nailed down to a T and tuned like a 1965 Shelby GT500. The company is generating healthy amounts of cash, and you sleep easy at night knowing you’ve played your part.

But if you barely even have time to sit down and eat your dinner, when are you able to seek out those capital allocation opportunities?

Great business owners know that effectively deploying cash generated from operations is more important to the company’s longevity than solely focusing on day-to-day activities. If you had two identical companies with one focused exclusively on operations, and the other on maximising shareholder value via effective capital allocation, the companies’ performance wouldn’t be marginal—but worlds apart. The examples and case studies we’ll use in this series will show how CEOs deployed capital to generate staggering long-term results—we’re talking about companies that outperformed the S&P 500 by 10x, 20x, even 30x, simply because the CEO mastered this skill.

Understanding how to create free cash flow and how to produce a return from it are two very different skills. Some people aren’t equipped with either skill, but a rare few have both. As business owners, it pays to understand where you lie on that spectrum.

Having cash in the bank ensures the company always has money at hand. How much is different from company to company. If you’re capital-light, then a couple of months’ operating expenses might suffice. If you’re capital-heavy, you’ll want more. Now, accumulating cash can be a strategic play—Buffett famously held billions waiting for the right opportunity. But there’s a difference between patient capital allocation and paralysis. If you’re keeping cash in the bank because you don’t know what else to do with it, that’s not strategy—that’s indecision. And indecision has a cost.

If you want to solidify the longevity of your company, you need to be thinking about capital allocation.

What Is Capital Allocation?

Capital allocation is how you—the business owner or CEO—deploy the company’s leftover cash after operating expenses, taxes and liabilities are taken care of.

The term “capital allocation” is typically used by investors to judge how well a CEO is utilising the company’s cash. The difference between a CEO who runs a Fortune 500 company and a regional construction business is that CEOs of publicly listed companies have to justify the decisions they’ve made to investors, their board and Wall Street. Private business owners are left alone with their decisions, unless there are other partners or external investors.

Now that we know capital allocation is how a CEO invests the company’s cash, the natural question is: what can they invest in? When you invest in something, you expect something in return, which is usually more than what you put in. But what can a CEO invest in—and what are these options that separate good capital allocators from great ones?

CEOs have five options to invest the company’s capital:

Invest in current operations,

Stock repurchases,

Pay down debt,

Acquire other businesses (M&As), and

Pay dividends.

There is a sixth option of doing nothing, which we’ve already covered above.

They also have three ways to finance capital: company cash, take on debt or issue equity.

Good capital allocation skills mean having the understanding of how to finance capital and knowing which of the above five options will generate the highest returns over the long term.

Let’s look at each of the five options.

1. Invest in Current Operations

Investing in current operations is typically the default option for when a company wants to use some of its excess cash. If you’re a construction company, you could decide to use the company’s cash to invest in new plant, tools and equipment, upgrade your company workflows to maximise productivity, or buy a company office instead of renting one. The chief goal here is to put your company’s cash to work so that the company is more efficient and productive, with the expectation that by doing so the company can generate a better return.

2. Acquire Other Businesses (M&A)

Acquisitions can offer a strategic competitive advantage that internal investment simply cannot achieve, and should be used when the expected rate of return from the other options is less favourable.

Acquiring another company can instantly give you access to new geographical locations, customers and product lines, and there are many different philosophies that companies deploy to achieve this. LVMH, the luxury conglomerate, owns 75 brands across six different sectors. This diversification can act as an economic moat, but for others such as Constellation Software, they only acquire other companies who specialise in VMS (Vertical Market Software).

When an attractive company appears undervalued, acquiring said company can instantly eliminate competitors and open up their customer base to you faster than building internal products themselves could. But just like share repurchases, when a company overpays for an acquisition, this comes at a massive cost to shareholders for publicly traded companies, or to you and your partners in a private company.

In summary, an acquisition should be favoured when it’s deemed the fastest and most effective way to gain market share, roll out new technologies or enter new markets.

3. Pay Dividends

Another option at the capital allocator’s disposal is to issue a dividend. If the company is publicly traded, then shareholders invested in the company will receive dividends in line with the company’s dividend policy, weighted by share count and class. Some companies issue multiple or single dividends per year—known as dividend stocks—others sporadically, and some not at all.

If you are a private company and are also a shareholder of said company, when a dividend is paid, you receive an amount that is based on the percentage of the company you own. If you own 50% of the company and the company votes a £50,000 dividend, you will receive £25,000 before tax.

Whether you’re a company that’s traded on the NYSE or provide laundry services in a small English town, once a dividend is issued, you pay tax on it. Depending on your current tax bracket and the dividend amount, you could end up departing with an unhealthy amount to the taxman.

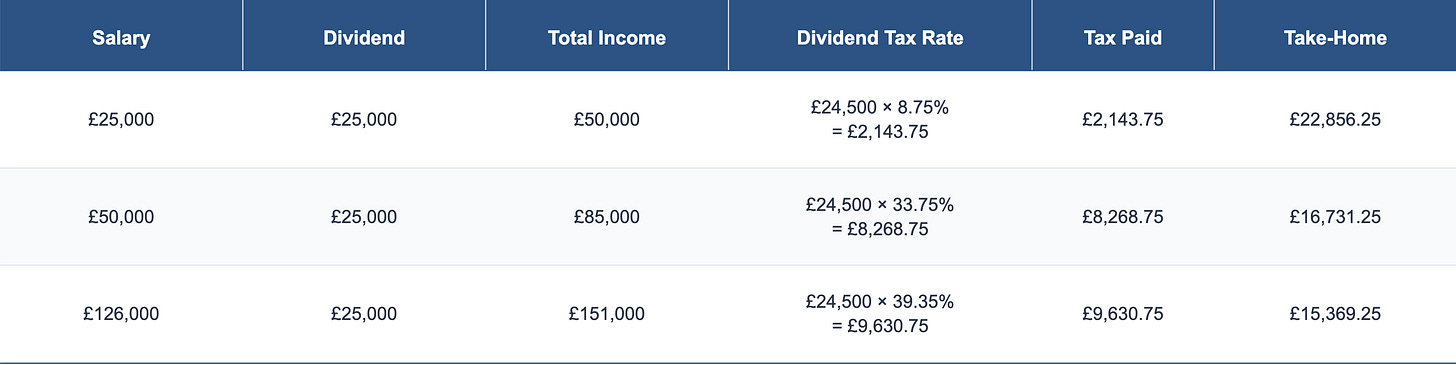

Let’s go through three examples to illustrate. In all examples, you and your partner decide that after a successful year you will issue a dividend to the tune of £50,000, or £25,000 each.

Taking the highest tax rate into account, you’ll pay nearly 40% out in tax. As a CEO or business owner, you have to ask yourself if this is the best use of capital allocation for the company.

I’m not saying don’t pay your taxes—just don’t pay more tax than you need to unless you need the money for something private, say a house purchase or side project.

4. Stock Repurchases

CEOs have two options when buying back stock:

They can either use cash on the balance sheet, or

They can use debt to finance the repurchasing.

The first option is more cautious, with shares typically being bought over a longer period of time when the stock is deemed cheap. The second option is usually done in the form of a tender, with a much larger purchase made in a single hit. The former is the equivalent of draining a reservoir via a straw—the latter a suction hose.

Both options can create long-term value for shareholders, and both options rely on the company’s stock being undervalued—but there is fundamentally a difference in conviction between both approaches.

However, it’s simply not enough for a CEO to buy back shares and think they’re doing a good job. Indeed, buying back shares that are overpriced is just about the worst thing you can do with the company’s money aside from burning it.

Private companies, of course, cannot buy back their own stock on the exchanges, but they can retire shares or buy out partners in part or in full.

5. Pay Down Debt

A CEO can decide to pay down company debt with excess cash. There could be a number of reasons why they would want to do this:

High cost of debt: Paying down high-interest debt provides a guaranteed, risk-free return on capital that is equal to the interest rate they are eliminating. If you have a company credit card that is paying 25% interest, then paying off this debt is more than likely better than the other options available to them.

Risk and financial flexibility: If the company’s leverage (debt-to-equity ratio) is too high or the company is worried about an economic downturn, then the CEO might play defensively and pay down debt. High debt also increases financial risk and the chance of defaults, and by reducing debt, the CEO improves the company’s credit rating, which in turn lowers the cost of future borrowing. If there is a recession, legal or regulatory disputes, then having low amounts of debt makes the company more resilient, which can mean taking advantage of opportunities (like cheap acquisitions) that financially strained competitors cannot.

Lack of high-return opportunities: The company has exhausted all other internal and external investment opportunities that would offer a return greater than the cost of debt. If the cost of debt is X and the expected return from all other options is less than X, paying down debt is the economically rational choice.

Final Thoughts

A well-run company is a cash-generating machine, and by now, it should be clear that being a good capital allocator requires the understanding of the multitude of options available to the business, and you, the CEO.

There isn’t one option from the five that’s consistently the best. Being a good capital allocator means understanding when to choose one over the other. Personally, for publicly listed companies, I think a dividend should be last on the list or not used at all so that the company can save up the excess cash for acquisitions. Many great capital allocators have done this, as alluded to before with Warren Buffett, who used Berkshire Hathaway’s subsidiaries to generate billions of dollars, which in turn bought more companies, which returned more billions to Berkshire.

In today’s essay, we’ve covered what a good business looks like, the two different types of CEOs, what capital allocation is, and the five options available to CEOs and business owners when it comes to investing the company’s leftover cash.

The next essay will explore the remarkable capital allocators featured in The Outsiders by William N. Thorndike. But here’s a snapshot: they didn’t follow the playbook. While their peers paid dividends because “that’s what shareholders expect” or made acquisitions to appear on magazine covers, these CEOs deployed capital with surgical precision—often doing the exact opposite of what Wall Street demanded. We’ll examine how they knew when to use each of the five strategies, and more importantly, when to ignore conventional wisdom entirely. The goal isn’t to memorise their moves, but to understand the thinking that let them recognise

Until next time, Karl (The School of Knowledge).

Whenever you’re ready

The School of Knowledge helps you understand the world through practitioners. Those who try, fail and do (skin in the game). 📚💡

Join our growing community of like-minded lifelong learners here: