It was the afternoon in Stromness, a small whaling town on South Georgia Island when somebody knocked on Thoralf Sørlle’s door. Sørlle, the factory manager answered the door and stood in front of him were 3 men. 3 men he knew weren't part of the whaling crew and that he could not recognise through the utter mess that they looked like. After a moment of disbelief, Sørlle spoke;

“Who the hell are you?” he said.

The man in the center stepped forward.

“My name is Shackleton” he replied in a quiet voice.

It is said that Sørlle stepped back and wept when he heard those words and any living thing with a heart would do better to not do the same. For Sørlle knew Shackleton. Shackleton had sought Sørlle’s advice in November 1914 when they arrived at Grytviken, a whaling station on South Georgia Island. 17 months earlier Shackleton and 27 other men had arrived on the British ship Endurance to begin the greatest of all Antarctic expeditions The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition.

Endurance by Alfred Lansing recounts one of the most extraordinary stories of mental fortitude, spirit and personal responsibility any human being could muster. It’s the unbelievable story of how 28 men were isolated in a place so remote and so untravelled it might as well have been on another planet.

The Hollywood ending is that all the men survive but between the start of the journey and the 17 months later to that knock on the door, it was anything but Hollywood. It was hell. A hell like no other with its minus 30-degree temperatures, colliding icebergs, hurricane-force blizzards and a sea like no other on Earth with its 100ft waves. Worse than all of the torment and desolation around them was the utter hopelessness of their situation.

They were isolated. Alone. Waiting for death to come take them away from this dire misery.

Until that moment when this man claiming to be Shackleton knocked on his door, Sørlle, the British and anybody else who cared to take an interest in the expedition assumed them dead. Lost to the notorious Weddell Sea or smashed to pieces by one of the hundreds of icebergs. For their mission was long over and not a soul had seen them since they left. It was not even worth contemplating that anybody, let alone 28 men could survive the inhospitable surroundings they were subjected to for that long. But there was one man who did believe that they could make it, he had to.

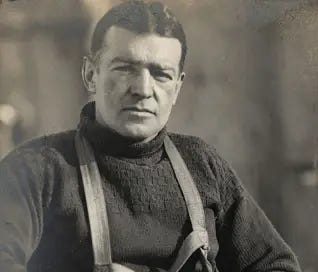

That man was Ernest Shackleton.

For scientific leadership give me Scott; for swift and efficient travel, Amundsen; but when you are in a hopeless situation, when there seems no way out, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton

Ernest Shackleton was a British explorer who twice before had attempted the race to the South Pole. One with Robert F. Scott in 1901 and 1907 when the expedition led by Shackleton got to within 97 miles of the pole. Then in 1912, Norwegian Roald Amundsen reached the South Pole. Shackleton had failed to engrave his name amongst the great explorers. But there was one last great Polar journey that could be made. The crossing of the Continent. It was this that Shackleton was to finally cement his name amongst the great explorers.

Right from the start you get an insight into Shackleton’s mindset. Upon deciding on this great adventure and convincing people to part with their money in support of it came the task of selecting the men. Ordinarily, this could be seen as a meticulous undertaking, after all the select men on board would all be called upon to play their part and support the expedition. There was no room for passengers in the Antarctic. No records of the interview process remain, if at all there was any with most interviews lasting only a few minutes. It seems that Shackleton went with his gut after asking peculiar questions to the men who in the end were selected because of matters such as whether could they sin!

That intuition, feeling or whatever else you want to call it would be called upon almost daily over the 17 months. That gut feeling he had, which so many times went against what his men were telling him would end up ensuring the 28 of them all went home.

The Norwegians, who were amongst the best seagoers in that part of the world advised Shackleton that the Weddell Sea and its surrounding ice was the worst that anyone had ever seen it. Shackleton decided to wait a little longer and this was one of the first signs of Shackleton’s knowledge of second-order thinking. He could look past the immediacy of his actions.

In 1903, some 12 years before becoming trapped himself stores were left on Paulet Island after a Swedish vessel became stuck in the ice pack. It was Shackleton who commissioned those stores. Whilst awaiting departure in 1914 he didn’t just sit on his hands, although eager as he were to get going. He sought the counsel of Thoralf Sørlle and his Captains to get a better idea of how the Weddell Sea and the ice operate.

When the ship finally did depart Shackleton summed up his feelings in his diary “Now comes the actual work itself… the fight will be good.”

Indeed it will.

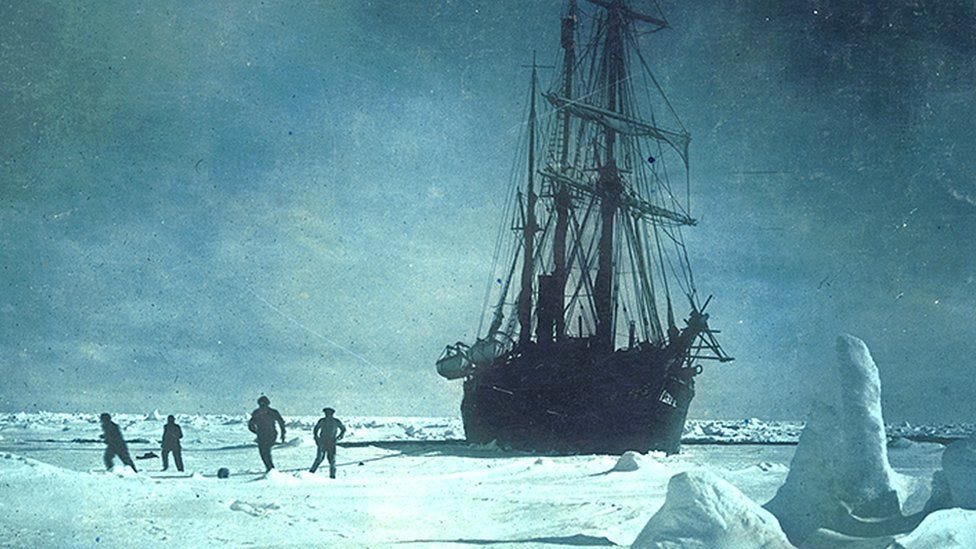

Again and again, she slammed into the ice, throwing a wave of water up over the floe, then staggered and rolled and slipped backward. At last on February 24 Shackleton admitted that the possibility of getting free could no longer be seriously considered. The sea watches were canceled and a system of night watchmen was instituted.

The Endurance had been beset for exactly a month, wedged between the uncompromising ice. The men had tried in vain for weeks and weeks to dig, shovel, and smash their way out but it was no use. Shackleton knew that they were just wasting resources including their energy in trying to break free so he decided to bunker down on the ship for the oncoming winter.

The routine on the ship was slow but Shackleton kept his men busy and understood exactly what was needed to keep morale as high as possible. Temperatures reached into the minus 30s as storms and blizzards battered the ship with the ice ever squeezing her from beneath.

By July the men were frequently tormented by something called ‘pressure’ from the icebergs and the noises it produced. Capable of ripping the ship into a thousand different pieces.

‘Lucky for us if we don't get any pressure like that against the ship for I doubt whether any ship could stand a pressure that will force blocks like that up.'

But they did.

The decks buckled and the beams broke; the stern was thrown upward 20 feet, and the rudder and sternpost were torn out of her. The water ran forward and froze, weighting her down in the bow, so that the ice climbed up her sides forward, inundating her under the sheer weight of it. Still they pumped. But at five o'clock they knew it was time to give up. She was done, and nobody needed to tell them.

Shackleton nodded to Wild, and Wild went forward along the quaking deck to see whether anybody was in the forecastle. He found How and Bakewell trying to sleep after a turn at the pumps. He put his head inside.

'She's going, boys,' he said. 'I think it's time to get off.'

The men departed the ship and set camp up on the cold ice that lay beneath them. Everybody went to bed except Shackleton who paced into the early hours of the morning assessing their new home. Then at 1 am a violent shock hit the floe and a crack started to appear. Right where their camp was. Shackleton hurried to wake his men and in the cold dark of winter in the Antarctic, they spent the next hour moving their camp for the second time in a few hours.

The next morning the mood in the camp was sombre with them all coming to terms with their new reality. Shackleton though, understood immediately what needed to be done for back in 1907 when he got to within 97 miles of the South Pole he had to turn back in a race against death because of a shortage of food. Many a man would have pushed on in the search of glory but Shackleton fully understood asymmetry more than most. He knew when the odds were stacked against him and he knew when they were in his favour.

Shackleton had decided that they needed to march to Paulet Island where the provisions and possible help were. Some 346 miles away across an untravelled part of the world carrying all they had to keep them warm and alive including their boats.

From studying the outcome of past expeditions, he believed that those that burdened themselves with equipment to meet every contingency had fared much worse than those that had sacrificed total preparedness for speed.

Shackleton told his men to ditch everything that would not keep them alive. He even theatrically threw his bible, which Queen Alexandra gave him into the snow.

Just before the journey, Shackleton confided in his diary 'I pray God I can manage to get the whole party safe to civilization.

The journey proved to be a disaster though. Carrying their personal belongings as well as the 3 boats over this rugged landscape proved too much. The men were taking turns in sledging 900 pounds and when fresh snow began to fall it made everything even harder. After a week, and a mile a day Shackleton knew it was a fruitless exercise and told the men they would retreat to Ocean camp from which they came and wait out the movement of the ice packs.

Teams were sent back to the Endurance to retrieve what stores and food they could and on November 21st, around a month of living on the ice, the remains of the Endurance finally sank beneath the ice and out of their sight forever. Now there was nothing to connect them to the real world. Nothing but ice in every direction for as far as the eye could see.

With the ice beginning to drift away from land Shackleton was beginning to become concerned ‘Of all their enemies - the cold, the ice, the sea - he feared none more than demoralization.’

Shackleton had made his mind up. They were to head immediately west leaving behind Ocean camp, one of their boats and a big chunk of their stores.

The journey was even more treacherous than the last. Shackleton and his men were making little headway and were continuously soaked from their own sweat and from falling through the ice beneath them, plunging them into sub-zero temperatures. Exhausted and deflated one of his men even refused to move until Shackleton talked him round. It was impossible to continue and Shackelton knew this:

‘Turned in but could not sleep. Thought the whole matter over & decided to retreat to more secure ice: it is the only safe thing to do…Am anxious: For so big a party & 2 boats in bad conditions we could do nothing: I do not like retreating but prudence demands this course: Everyone working well except the carpenter: I shall never forget him in this time of strain & stress.'

This is the second time Shackleton attempted to head for land and the second time he had failed. He even blamed himself for entering the ice pack that ultimately would beset the Endurance and encamp them in the middle of nowhere for the winter. But again Shackleton had shown an unbelievable ability to know when to fight and when to retreat. For all of Shackleton’s will and fight, this was not his fight alone and every decision he made was made in the hope of keeping all 28 of them alive.

By March time, some 4 months after the Endurance had sunk the toll of their new environment was beginning to show in the men. They were almost out of food and were looking likely to spend another winter in this horrendous environment. The smallest of things could cause the men to blare arguments or be on the verge of tears but throughout these testing times, one thing always remained within them. It was a togetherness and bond like no other.

We think of resilience and ‘grit’ today in a different way I think. We trophy waking up in the morning and making our bed and we think that we’re ‘committed’ when we tweet 5x a per for 30 days but here you have a group of men fighting for their lives day in and day out. Their almost a year and a half into this torturous experience, killing what animals they can find with their bare hands in a perpetual state of wetness in sub-freezing temperatures. Throughout the book, it’s utterly amazing to see that throughout all of this, they never turned on each other.

Well, not really.

Shackleton had hardly left when Macklin turned on Clark for some feeble reason, and the two men were almost immediately shouting at one another. The tension spread to Orde-Lees and Worsley and triggered a blasphemous exchange between them. In the midst of it, Greenstreet upset his powdered milk. He whirled on Clark, cursing him for causing the accident because Clark had called his attention for a moment. Clark tried to protest, but Greenstreet shouted him down. Then Greenstreet paused to get his breath, and in that instant his anger was spent and he suddenly fell silent. Everyone else in the tent became quiet, too, and looked at Greenstreet, shaggyhaired, bearded, and filthy with blubber soot, holding his empty mug in his hand and looking helplessly down into the snow that had thirstily soaked up his precious milk. The loss was so tragic he seemed almost on the point of weeping. Without speaking, Clark reached out and poured some of his milk into Greenstreet's mug. Then Worsley, then Macklin, and Rickinson and Kerr, Orde-Lees, and finally Blackboro. They finished in silence

There was a thunderous sound and crack, their floe had split down once too many times. What was once a mile-and-a-half-wide piece of ice was now an odd-shaped triangle no more than 50 yards wide. There was nowhere else to go. To stay would be catastrophic but to launch the boats is almost certain peril.

But what choice did they have?

“Launch the boats!”

They thought neither of Patience Camp nor of an hour hence. There was only the present, and that meant row get away... escape.

If anybody thought that what they had endured thus far was unfair or inhumane it’s nothing compared to the misery the men find themselves in now. Cramped into 3 boats no more than 22ft long each that are so unfit for the task that’s been thrust upon them it’s untrue.

But they row because their lives depend on it.

By late afternoon the men are exhausted and Shackleton decides to jump on a small floe to camp down for the night. The men turn into their wet tents and jump into their wet sleeping bags but none care. They begin to sleep almost immediately when Crack!!

There’s panic and confusion as the men try to orientate themselves in the dark of night and hurry the stores in the boats but there’s a problem. Somebody’s missing. Scurrying around Shackleton finds the crack had swallowed up a tent. A tent with somebody in it was now submerged and tangled in the freezing water. Shackleton reaches down and heaves the tent up with all his power. Ernie Holness was sodden but alive and there was no time to waste in getting off this floe.

They made a pitiable sight three little boats, packed with the odd remnants of what had once been a proud expedition, bearing twenty-eight suffering men in one final, almost ludicrous bid for survival. But this time there was to be no turning back, and they all knew it!

The men aboard the 3 small whaling ships were now up against a formidable opponent. Unlike the ice floes they could survive, and almost thrive on. They could hunt for food and keep themselves relatively busy but here in the open sea they were just holding on and holding out for as long as they could. For at any moment, one of the 90ft waves could bring down upon them millions of tonnes of water.

Conditions were so horrific that it seems hard to comprehend how anybody could survive. But they had to. Many of the men were bent into a constant half-sat up half sat down position, some had boils and blisters the size of footballs on their backsides but all of them were wet. Perpetually wet. The water that filled the boats had to be bailed out constantly and was always about ankle-deep. Their wet sodden feet would often start to freeze when the temperatures dropped. One man, Blackboro ended up with severe frostbite that later on in the story would mean them amputating his foot.

On an island. In the middle of nowhere.

But then they saw it. Unmistakable land. 497 days had passed since they last stood on it and shortly would stand on her again.

After they landed the men almost all fell where they stood to sleep. But there was another cruel twist in this story. In less than 24 hours they would be back on the open sea to try and find a better place for where they had landed offered them nothing but a temporary reprieve.

Time and again the men on this expedition were seemingly dealt the cruellest of hands but often through the book you are taken back not only by the sheer bravery of the men and of Shackleton’s leadership but by their ceaseless attitude and commitment to enduring the most horrific of circumstances. At times they almost seemed to revel in it!

The next plot of land didn’t offer them much more and many of the men were seemingly on the brink of death. Shackleton decided that he and 5 others would leave camp to try and find help.

Again Shackleton was back on the water and this time, if possible, conditions were even worse. The men they left behind on Elephant Island had to endure hurricane-force winds but they were somewhat sheltered after making a makeshift hut. Shackleton and the 5 others were not.

Conditions on board the boat got so bad that at one point they had to anchor, however, the boat froze within the ice. The men were battered by the waves and freezing to death, but they had to take turns crawling up to the front of the boat to hack away the solid ice before their boat became too heavy. Holding on for their lives as wave after wave-battered them from above. This became their reality.

The sight that the Caird presented was one of the most incongruous imaginable. Here was a patched and battered 22 foot boat, daring to sail alone across the world's most tempestuous sea, her rigging festooned with a threadbare collection of clothing and half-rotten sleeping bags. Her crew consisted of six men whose faces were black with caked soot and half-hidden by matted beards, whose bodies were dead white from constant soaking in salt water. In addition, their faces, and particularly their fingers, were marked with ugly round patches of missing skin where frostbites had eaten into their flesh. Their legs from the knees down were chafed and raw from the countless punishing trips crawling across the rocks in the bottom. And all of them were afflicted with salt-water boils on their wrists, ankles, and buttocks, But had someone unexpectedly come upon this bizarre scene, undoubtedly the most striking thing would have been the attitude of the men relaxed, even faintly jovial - almost as if they were on an outing of some sort.

Mile by mile they endured and for 13 days and nights the sea, the wind and the Antarctic had thrown everything she had at crushing this pathetic 22-foot boat. With each hour the men grew in belief when wave after wave after wave crashed into them. But they were still there, they were still fighting. Land was in sight and they became almost deranged in their commitment to get there.

But sufficiently provoked, there is hardly a creature on God's earth that ultimately won't turn and attempt to fight, regardless of the odds: In an unspoken sense, that was much the way they felt now. They were possessed by an angry determination to see the journey through - no matter what. They felt that they had earned it. For thirteen days they had absorbed everything that the Drake Passage could throw at them and now, by God, they deserved to make it.

Finally, on May 10th 1916 at five o’clock they were standing at last on the island they had set sail from 522 days before.

Almost in disbelief but more so from exhaustion, the men shook hands. There was no celebration. They had endured the first part of the journey for now Shackleton had decided that the next best thing to do would be to cross over land 29 miles to where a whaling station would be.

3 men would stay and 3 would go.

Men had been coming to South Georgia for 3/4’s of a century and not one man had ever done what Shackleton was proposing to do simply because it could not be done. The peaks of the rugged iced mountains were about 10,000ft which ordinarily by climbing standards are not particularly high but they were almost impassable. The clothes they had were threadbare and each man mentally and physically was spent in every which way imaginable.

But what could they do?

The 3 men set off on this impossible journey. Traversing snow-capped mountains with no obvious route to where they were going, only estimates. Time and again they came to an impasse and would have to retrace their steps and start again. A cruel attempt at the Antarctic to force them into some sort of maze game. But Shackleton wasn’t in the mood for games. His life, and I believe more importantly to him the lives of all of his men counted on him now more than ever. Everything Shackleton had done thus far had kept himself and his men alive but that caution, which earned him the nickname ‘Old Cautious’ was thrown to the wind.

With the nighttime and subsequent freezing temperatures chasing them they were barely keeping pace ahead and Shackleton knew that if they could not find lower ground they would freeze to death. Understanding the dire situation he found themselves in, Shackleton said something to which the other two men thought he had lost his mind, for what he was saying could not be coming from ‘Old Cautious’’ mouth":

Speaking rapidly, Shackleton said simply that they faced a clear-cut choice: If they stayed where they were, they would freeze - in an hour, maybe two, maybe more. They had to get lower - and with all possible haste.

So he suggested they slide.Worsley and Crean were stunned especially for such an insane solution to be coming from Shackleton. But he wasn't joking... he wasn't even smiling. He meant it - and they knew it.

The 3 men linked around each other’s waists with their legs all aware that what they were doing was surely suicide. The drop was 2000 feet below them but they didn’t have a choice. So they went for it.

Then they shot forward onto the level, and their speed began to slacken. A moment later they came to an abrupt halt in a snowbank.

The three men picked themselves up. They were breathless and their hearts were beating wildly. But they found themselves laughing uncontrollably. What had been a terrifying prospect possibly a hundred seconds before had turned into a breathtaking triumph.

They looked up against the darkening sky and saw the fog curling over the edge of the ridges, perhaps 2,000 feet above them - and they felt that special kind of pride of a person who in a foolish moment accepts an impossible dare - then pulls it off to perfection.

Shackleton and his two other men would reach the whaling station in under 36 hours. It would not be until 1955 that another human would do so again. The expedition in 1955 did so with the latest technology and the comfort of air travel helping them navigate the best routes. Shackleton did it with 50 feet of rope and a carpenter’s axe.

‘I do not know how they did it except that they had to.’

It would be another 3 and a half months before all of the men are rescued. Shackleton was there until the very last man was safe and accounted for.

‘In appreciation for whatever it is that makes men accomplish the impossible.’

Personal Thoughts

This book is incredible. There’s something about reading about great expeditions like this that I find fascinating. It’s not too long ago but these men didn’t have the luxury of 2024’s technology or knowledge of our Earth. It really was the blind leading the blind.

There’s almost not a place on Earth that’s not been explored, picked and prodded. There’s almost no romance in travel and exploration just routine.

But this wasn’t routine for Shackleton. This was alien.

One of the aims of this newsletter is to read about and from the best thinkers, leaders and doers of the last few thousand years and try to distil down some actionable insights that can help us ordinary folk in everyday life.

But how can I do that with this story?

I have the luxury of having a somewhat similar experience of some of the conditions Shackleton had to endure for back in 2010 I had just passed out as a Royal Marines Commando and was sent to Norway for Artic Weather Warfare Training.

Temperatures too were as low as the minus 30s. I even had to jump in a lake where 2 feet of snow was cut out creating a hole but even then after submerging yourself and your equipment for a period you get out, get to the dry tent rechange and warm up. Shackleton didn’t have that. To be constantly wet can have an enormous effect on a person’s mental wellbeing and morale. Again something I had to endure frequently but not like this and not for this long.

You can’t fake leadership. You even have it or you don’t and people will see right through you. One thing great leaders do though is they lead. They set by example and I believe it’s this more than anything that ‘Sets men’s souls on fire’.

When someone is the first to volunteer themselves to something so outrageous it borders insanity when there is no reason to volunteer themselves first, if at all. That’s what inspires men. That’s what makes people follow you.

Shackleton was excellent at two things:

Second-order thinking

Understanding asymmetrical bets

His self-confidence bordered on aloofness and arrogance at times but his conviction was absolute. At any time life could have taken him and this great story away from us and lost forever but I’d like to finish with a quote by Nassim Taleb in regards to heroes and how we think about them wrong. Shackleton would have been a hero even if they had not survived because his actions and leadership were what heroes did. Heroes don’t just win, they lose too and we’ll do well to remember all the people who day in and day out do the right things and don’t win.

Heroes are heroes because they are heroic in behaviour, not because they won or lost.