Learn How to Become a Systems Thinker

What an ancient story can teach us about our modern lack of systems understanding

Beyond Ghor, there was a city. All its inhabitants were blind. A king with his entourage arrived nearby; he brought his army and camped in the desert. He had a mighty elephant, which he used to increase the people's awe. The populace became anxious to see the elephant, and some sightless from among this blind community ran like fools to find it. As they did not even know the form or shape of the elephant, they groped sightlessly, gathering information by touching some part of it. Each thought that he knew something because he could feel a part...The man whose hand had reached an ear said: "It is a large, rough thing, wide and broad, like a rug." And the one who had felt the trunk said: "I have the real facts about it. It is like a straight and hollow pipe, awful and destructive." The one who had felt its feet and legs said: "It is mighty and firm, like a pillar." Each had felt one part out of many. Each had perceived it wrongly....

This ancient Sufi story was told to teach a simple lesson but one that we often ignore: You can not understand the behaviour of a system just by knowing the individual elements that make up the system.

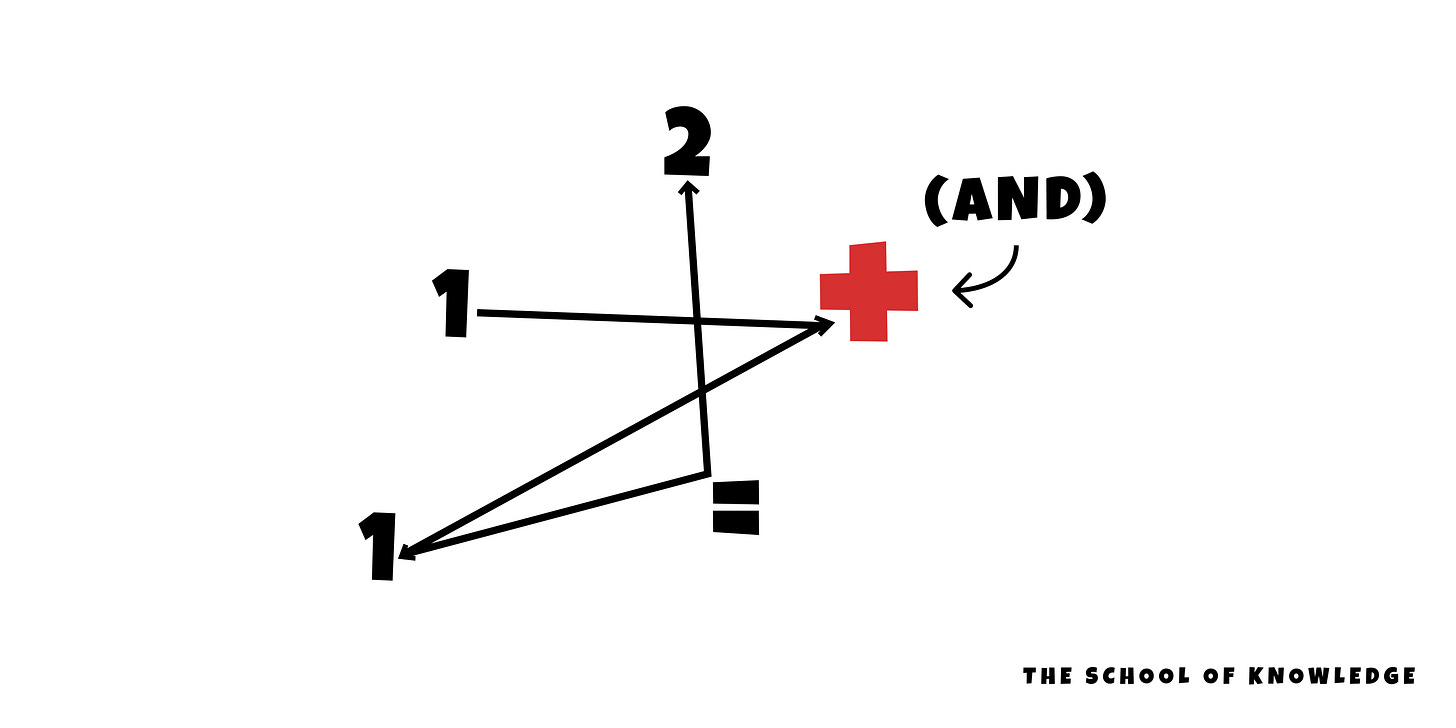

You assume that because you understand ‘one’ and that one and one make two, you must understand ‘two’. But a system is more than just the sum of its parts. You need also to understand, ‘and.’

This is the foundation of basic systems thinking, which Donella H. Meadows lays out in her famous book, “Thinking in Systems.”

Today, we’ll learn what systems are, how to identify them and how an ignorance of systems understanding costs us every day.

What is a System?

Systems are a set of things called elements that are interconnected and interact with each other to produce a response, behaviour or pattern over time. Systems can be influenced, driven, triggered or constrained by external forces, but their response to this is characteristic of the system itself and is seldom easily understood until retrospectively. This is why no one can predict inflation movement until inflation has happened, regardless of what people who want you to believe them say.

You can think of systems as living, breathing things that ebb and flow over time like the tide and can exhibit goal-seeking, self-preserving, dynamic and adaptive behaviour.

The elements in a system can change, but the system as a whole will not. Imagine a football team as the system, with the individual players as the elements. You can change a player, and the system remains mostly the same. When you change all of the elements (players), you may change the behaviour of that team, but you will still have a system. It’ll just act differently.

But to understand systems, you have to understand the relationship between the structure and its behaviour. Long ago, we had to understand complex systems in the world around us. Our bodies, new languages, currency, seasons, the Earth’s orbit around the sun, and which fruits you can eat and which will kill you are all examples of complex systems that people had to understand to get by.

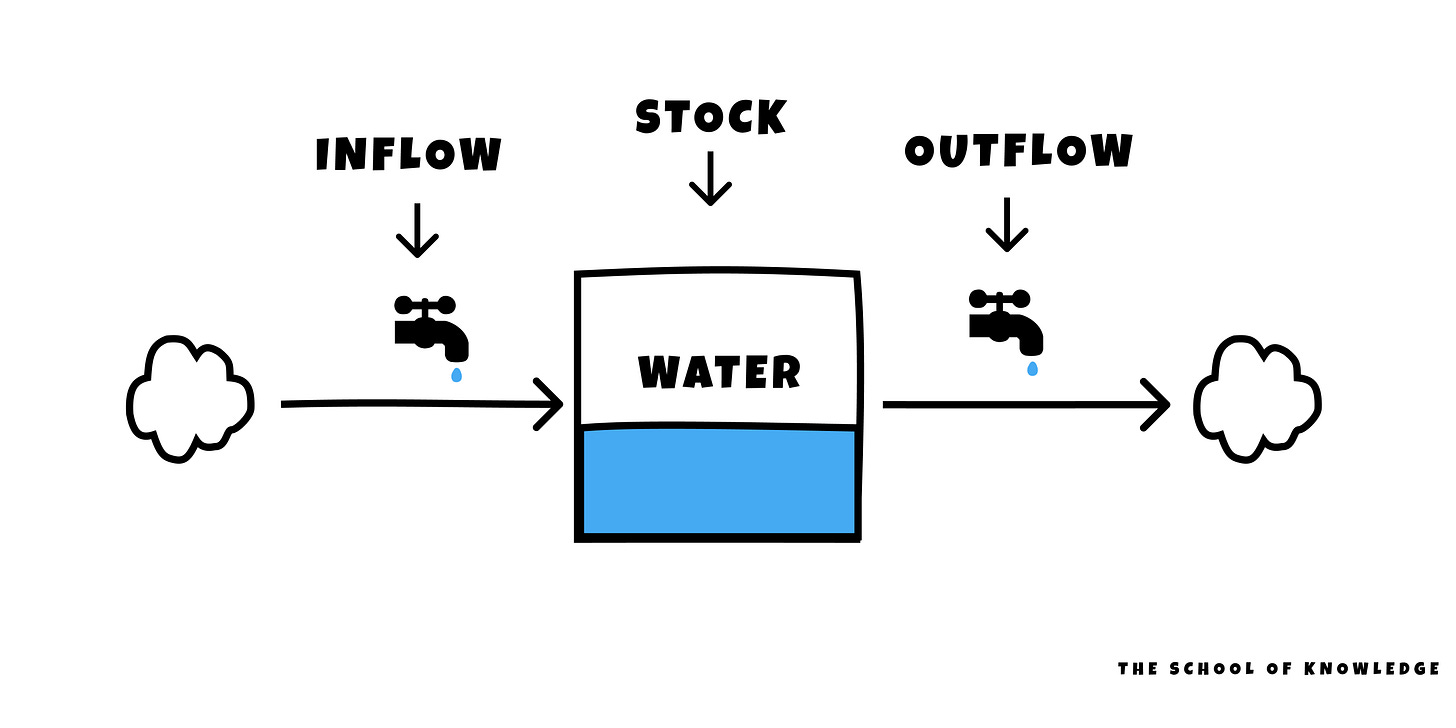

A stock is the foundation of a system. Stocks are measurable elements of the system that have built up over time. A stock can be the stock price of a listed company, cows on a farm, points a football team have accumulated over a season, books in a library, or the population of a country. Stocks don't have to be physical, either. An anxiety about flying or your reputation as an arms dealer counts as stock.

Stock can change over time and are influenced by inflows and outflows. Think of the inflow of illegal weapons into a country that has overthrown its government as nefarious agencies wrestle for power or the outflow in the number of cows after a bout of mad cow disease. The stock level can dramatically change with flows. A stock at any given time represents the history of the flows within a system.

Through the inflow of water, a bathtub’s water level increases, but it takes time to fill it up to the desired level. It has a lagging effect. This is how reservoirs operate. When there’s a drought, you can’t crank up the inflow of rain, so what do you do? You reduce the outflow to keep the reservoir at a desired level. We find it easier to focus on inflows rather than outflows, but you can often get the same result by adjusting either. If you are struggling to ‘find the time’ to do something, perhaps you could look at adjusting the inflow from other activities and tasks you are currently doing.

It's important to understand how lagging flows can affect systems. Because the behaviours take time to adjust to the flow rate of a system, it can offer stability and opportunity, so long as you understand how long that lag should be.

You don't give up too soon.

If a farmer in Norway wants to start a company that sells Christmas trees, she’ll more than likely need to start planting trees a few years before she can even sell her first tree. She will also need to keep planting trees (inflow) each year for when her stock depletes as people buy their Christmas trees (outflow) from her. If she had given up after one year, it would have been a complete waste of time and shortsightedness on her behalf. A better system would be to find an existing farmer to buy and upsell Christmas trees from as her stock grows in the first few years.

“A stock takes time to change because flows take time to flow. That's a vital point, a key to understanding why systems behave as they do.”

- Donella H.Meadows

When you begin to notice the behaviour of a system, you will start to notice that there are things that can affect the level of a stock. These are called feedback loops, and in systems, there are typically two kinds.

Balancing feedback loops are designed to keep the stock at a desired level. With digital thermostats today, when your thermostat is set to 21 degrees and this temperature is reached, it will turn off. It doesn’t let it skyrocket up infinitely. Balancing feedback loops is goal-seeking or stability-seeking.

Reinforcing feedback loops are self-enhancing and can lead to exponential growth or rapid collapses. These are found when the stock can reproduce itself. When governments heavily quantitive ease, which is to say, print money, it is quite often followed by a rapid balancing loop such as inflation. The Zimbabwe government famously hit hyperinflation in 2008, where inflation hit 79.6 billion percent!

So now you understand the effect the inflows, outflows and two feedback loops have on the behaviour of a system. What’s even more important to understand is that the behaviour is only seen once it has occurred. When you notice the behaviour of a system as a consequence of the flow rates and feedback loops, adjusting either of them will not stop that current behaviour. At least not yet. Remember the lagging effect?

Going back to the quantitive easing analogy, when governments print (make up) money and distribute it to its people, such as when Covid kept us all from working, it can’t go on forever. There had to be a balancing loop. The money becomes less valuable because more people have it. When more people have more money, but the distribution of products and services remains the same or decreases, prices go up. When prices go up, the people who can afford them pay for them, and people who can’t demand wage increases. When they get a pay rise, they begin to pay for things again, and thus, this cycle of price wars, wage increases, and inflation continues until the good old bank of wherever raises interest rates to curb the exponentially growing inflation.

So why is it that somebody had to write a book about systems thinking when we were pretty good at it already way back then? Well, the world is just far more complex than it’s ever been, and the systems are so interconnected together it’s like a giant spider web interleaved around the Earth. When we were hunter-gatherers, we needed to deeply understand the systems around us because our lives literally depended on it. Eating the wrong fruit or not being prepared for adverse weather was the difference between life and death. Understanding how more money for more people leads to more inflation for more people isn’t on the same level, but a lack of systems understanding does make people poorer, more miserable and slaves to their lack of systems understanding.

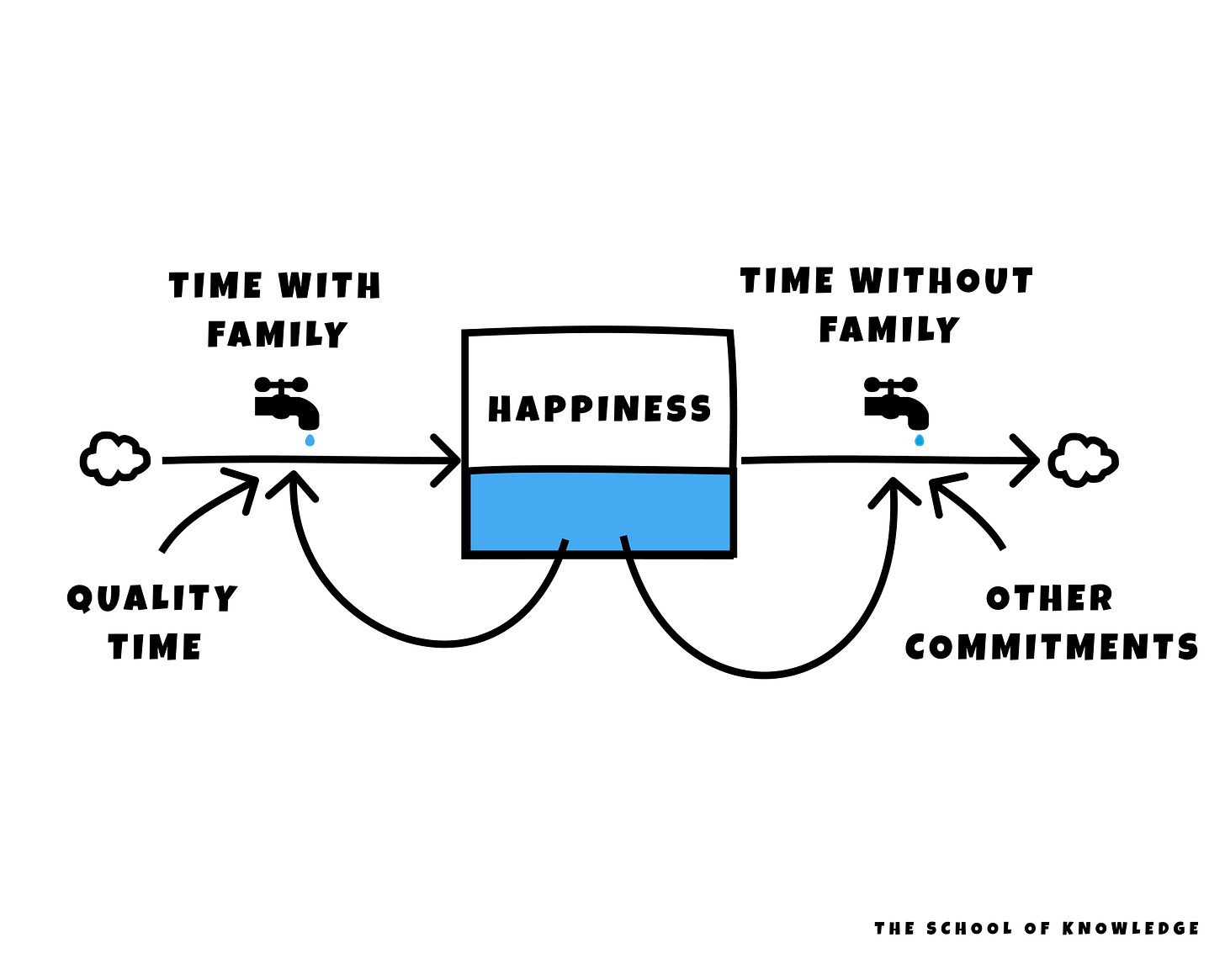

If you’re unhappy and want to know how you can change that, having a basic understanding of systems can help you. Your happiness (stock) is affected by the totality of things (elements) in your life. You know that to have more of one, you need to adjust the inflow rate or decrease the outflow rates of others. You also know that there are reinforcing feedback loops to help you crank something up and balancing feedback loops to help you constrict or stabilise another.

James Clear summed up the importance of systems thinking brilliantly:

“You do not rise to the levels of your habits but fall to the level of your systems.”

Until next time, Karl (The School of Knowledge).

Whenever you’re ready

The School of Knowledge helps you understand the world through practitioners. Those who try, fail and do (skin in the game). 📚💡

Join our growing community of like-minded lifelong learners:

It's not just flows. It's also emergent behavior, -- new flows, and new stocks, if you will -- that make this complex

Thank you for sharing this. It is an insightful read. Only one feedback - In some places, you have jumped from one example to another. It would be great if you could dive deeper into one or two examples and explain each part of the system in the next pieces. Thank you 🙏