21 Thinking Tools for Making Better Decisions

Interesting concepts, mental models & frameworks

Welcome to the The School of Knowledge and this week’s free essay. Each Sunday, I send an essay to help you navigate your personal or professional transition, from those who have tried, failed and succeeded—those with skin in the game. If you want support on how to implement the mental models, frameworks, and systems, take part in Q&As and have access to our private chat, consider becoming a paid member.

When facing life's complexities, you want to move beyond making decisions based solely on gut feelings. Your path forward isn't about gathering more information, but developing stronger mental processing systems that transform existing knowledge into better decision-making capabilities. Life is great at throwing curveballs at you, but by having frameworks, models and concepts to use at your disposal, you go from navigating in the dark to light.

When you start weaving these frameworks together, decision-making stops feeling like educated guesswork and starts feeling like something you can get good at.

Below are 21 mental models, concepts and frameworks I use to help me make better informed decisions and hopefully to get you thinking better:

1. Bounded Rationality

Humans make reasonable decisions based on their information, but they often fail to adjust, consider, or discount information that has not yet been seen (future) or exists in the distant past. We use the limited information available to make decisions we can live with, changing our behaviour only when necessary. People tend to exaggerate present information, such as current events, while discounting future risks that don't seem relevant to them. This is why individuals struggle to understand complex systems; they ignore the past and pay no attention to the future.

Why it's important: Traditional economics assumes people make optimal decisions with perfect information, but this concept, developed by Herbert Simon, shows why real human behaviour is different. Understanding bounded rationality helps explain why we use mental shortcuts (heuristics), why we sometimes make “irrational” choices, and why satisficing (finding something satisfactory) often beats maximising (finding the perfect option).

2. Circle of Competence

Your circle of competence represents the areas where you have genuine knowledge, expertise and judgement. It’s the edge of what you know you understand vs what you only think you understand.

Famed by the late Charlie Munger and business partner Warren Buffett, it reminds individuals to stick to what they know best. This isn't just true for investing but for all walks of life. You'd be foolish and, in fact, more than likely dead, if you tried to be an Alpine climber if you'd never climbed before.

Why it's important: It’s tragic to see mistakes being made by people who have no credibility or right in making those decisions in the first place. Yet in spheres such as politics, you have incapable people placing heavy bets with somebody else’s money. If you have people making big decisions in things they know little about, AND where the consequences of getting it wrong are personally small to nil, you don’t have a thunderstorm brewing—you have a category 5 hurricane.

3. Anti-fragility

Anti-fragility is a concept where things get stronger from stress, disorder or challenges. Nassim N. Taleb developed a triage for how things respond to stress:

Fragile: Things that break under stress (like a glass vase that shatters when dropped)

Robust: Things that resist stress and stay the same (like a rubber ball that bounces back)

Anti-fragile: Things that improve under stress (like your muscles getting stronger after exercise)

Why it's important: This concept helps you understand that stress, chaos and challenges shouldn’t be something to be avoided, but in fact, welcomed. There are times when you shouldn’t seek chaos, such as in your relationships, but there are other areas of your life where growth, opportunity and chance meet at the intersection of what you think you are capable of and not. Overprotection of one’s ego, resources or commitments isn’t a show of organisational superpowers but a vulnerability for when the cards do fall.

4. Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias is our brain's tendency to seek out evidence that supports our existing beliefs while ignoring or dismissing contradictory evidence.

People who favour one political party over another champion their side’s policies, regardless of whether they believe in them or not.

Why it's important: Confirmation bias powerfully shapes how we see the world without us realising it. It creates a distorted reality where we think we’re being objective, but we’re trapped in a loop of self-reinforcing beliefs. This affects everything from personal relationships to major societal issues like politics and science. Science once stood for absolute truth, but has become increasingly politicised because of people’s bias towards their parties.

We would all do well to learn from Charles Darwin, who spent the majority of his life trying to find ways in which what he believed was false.

5. Critical Path Method

A step-by-step project management framework for identifying essential tasks that determine the minimum project duration.

Imagine building a house: you can’t build the brickwork before the foundations have gone in, but you can paint different rooms, lay the floor, or hang doors at the same time.

Why it's important: The Critical Path Method helps you focus on the tasks that truly matter for staying on schedule. If tasks on the critical path get delayed, the whole project is at risk of being delayed as you fight to try and claw back time. This framework prevents wasting resources on less urgent tasks and helps identify which delays are worth worrying about. It's the difference between panicking over every small setback versus knowing exactly which problems need immediate attention to keep a project on track.

6. Decision Journal

A decision journal is a record where you write down important decisions before you make them, including what you expect to happen and why. Later, you come back and see if things turned out the way you thought they would.

Unlike a diary, where you write about your day, a decision journal is structured. You state a decision you are about to make, why you are making it and what you expect to happen and come back to it over time to see how it turned out in reality.

Why it's important: Our memories trick us. We often forget why we made decisions or convince ourselves we knew what would happen all along (when we didn't). A decision journal keeps a painfully honest record of your thinking process.

7. Deliberate Practice

A structured training methodology designed to improve performance through focused effort on specific weaknesses or areas needing improvement. Unlike regular practice, where you just repeat something you already know how to do, deliberate practice pushes you just beyond your current abilities, uses focused attention, and requires feedback on how you're doing.

Sport offers an easy analogy because it’s easy to visualise the Michael Jordans, Ronaldo’s and Tom Brady’s perfecting their craft one small iteration at a time for hours on end, but deliberate practice can be used for almost anything so long as it pushes you beyond your limits and has immediate feedback. Learning to play musical instruments is another example.

Why it's important: Deliberate practice explains why some people become extraordinary at what they do while others plateau despite years of “experience”. It’s important to note that simply doing a thing over time will not automatically make you great. It’s how you use that time that truly matters.

8. Growth vs Static Mindset

A concept that distinguishes between seeing abilities as dynamic versus static. Famed by Carol Dweck, a growth mindset is believing that your abilities are fluid and not fixed—they can change over time. A fixed mindset is believing that your abilities are fixed—what you're born with is what you have for life.

It’s easy to see the flaw in a fixed mindset from the get-go. As babies, we’re born with no talents. What we deem as our abilities as adults is a culmination of what we learnt as kids or early adults. If we have bad learning habits, it makes sense that we might be poor at something.

Why it’s important: You’re mindset has been proven to dramatically influence how you approach challenges and react to failures, and simply believing that your abilities can change for the better automatically puts you ahead of people who don’t.

9. Hanlon's Razor

This concept suggests we shouldn't attribute to malice what can be adequately explained by incompetence. Our brains are quick to assume bad intentions, and Hanlon’s Razor asks us to pause before jumping to negative conclusions and states that most mistakes people make can be attributed to carelessness, misunderstandings or thoughtlessness.

Why it’s important: Hanlon’s Razor helps you stay grounded and avoid paranoia by staying more rational and avoiding automatically believing that people always have bad intentions. A good one to remember for personal and professional relationships.

10. Ikigai

Ikigai is a Japanese idea that represents the sweet spot where four elements of your life overlap: what you love doing, what you’re good at, what the world needs, and what you can be paid for. It's often described as “your reason for being” or “what gets you out of bed in the morning.” The idea is that when you do activities that fit in the middle where all circles meet—things you love, excel at, can earn money from, and that helps others—you’ve found your Ikigai.

Why it’s important: The concept of Ikigai has been hijacked by Western thought, but it still offers a beautiful framework for finding a balanced and fulfilled life that goes beyond “making loads of money” or “just follow your passion.”

One of my most popular pieces discusses it in more detail below:

11. Epistemic Rationality

When you say “I believe there will be a world recession in 2026,” you are engaging in thinking that concerns epistemic rationality. But, how do you know what you believe is true? This skill, and that’s what this is, is about accurately matching your beliefs with that of reality. It’s about figuring out what’s true, rather than what you wish were true or what sounds popular.

Why it’s important: Our brains are full of biases and shortcuts that distort our thinking and understanding of reality. Today, more than ever, it’s dangerously important to make sure you back-check information you are told and information that you readily believe. For those interested, the following concepts help explore this topic in more detail: Bayesian reasoning, calibration training, falsification, steelmanning, double crux and explicit bet-making.

12. Instrumental Rationality

When you ask yourself, “How can I grow my business’s revenue?” you are engaged in thinking that is considered Instrumental Rationality or simply, how do I make better decisions to achieve my goals? It is the skill of taking effective actions to help you determine the most efficient path.

Why it's important: Having accurate beliefs (epistemic rationality) is only useful if you can translate those beliefs into effective action. Many people know what they should do, but still make choices that work against their own goals. Instrumental rationality provides frameworks for avoiding common decision traps such as preference clarification, value of information analysis, implementation actions and goal factoring.

If you’re interested in Epistemic and Instrumental Rationality and would like an essay diving deep into one of them, please let me know in the poll below:

13. Inversion

Legendary investor, Charlie Munger, is infamous for saying Whenever you face a problem, you should ‘Invert, always invert.’ Inversion is approaching problems backwards (what could make this fail?) rather than forwards, to identify hidden obstacles and blind spots to avoid.

Imagine planning a camping trip. Rather than itemise everything you can remember you need, inversion asks you to consider “what would ruin this trip?” You would automatically think of the weather and not having adequate clothing, running out of food or water, having no sleeping bag, etc, leading you to pack adequate clothing, food and a sleeping bag.

Why it's important: It’s a lot harder to sit there and think of how to do something. Questions such as “how can I lose 3 stone in 6 months,” or “how can I learn Spanish in 12 months,” can often lead to procrastination and overwhelm. It’s much easier to list all the things a healthy person would do, such as being aware of their calorie intake (and having the means to track it), eating whole foods over processed and exercising a few times a week. Likewise, what would somebody bad at learning Spanish do? They’d never practise deliberately. They’d go days or weeks in between sessions, and they wouldn’t reflect or test themselves to see if they’re making progress. In the first instance, do what a healthy person would do, and in the second, don’t do what somebody badly learning a language would.

14. Kintsugi

Kintsugi (“golden joinery”) is the centuries-old Japanese practice of repairing broken pottery by highlighting the areas of breakage with lacquer mixed with powdered gold, silver, or platinum. Unlike most repair methods that aim to hide damage, Kintsugi deliberately highlights the fractures.

Why it's important: We live in an age that promotes perfectionism. Our social media platforms are snippets taken only from the moments in life we want people to see. How vain have we become. Yet again, the Japanese offer a practical philosophy that focuses on highlighting the fractures rather than trying to hide their flaws. It’s a powerful metaphor for how we can approach life’s challenges and teaches us that our fractures, cracks and leaks don’t need to be hidden but can indeed become our greatest strengths.

My last post dived deeper into this topic:

15. Maker vs. Manager Schedule

A manager’s schedule is filled with hourly blocks, meetings and the coordination of people, resources and decisions. Their days can often be fractured. A maker’s schedule abhors such schedules and instead requires uninterrupted blocks of time to create things, with even one ‘quick’ meeting ruining their concentration and flow.

Why it's important: Understanding the difference between these two fundamentally different approaches to time management can help organisations design better workflows. The distinction helps individuals recognise which schedule type they need for different tasks, and the maker’s schedule offers a framework for structuring time according to different types of work requiring different attentional patterns.

16. Minimum Viable Progress

A concept for breaking down goals into the smallest meaningful steps that demonstrate forward momentum. Our brains love doing nothing at all (leading to procrastination) or trying to do everything at once (leading to burnout.) MVP is about finding a balance between doing nothing so small it feels pointless and something so ambitious you’ll never finish it.

If you decided to write a book, after the initial excitement, you might be met with dread and questions such as “how on earth am I going to finish this?” But a typical book is roughly 300 pages. If you wrote one page a day (about 250 words) in 300 days, you would have a draft for your book.

Why it’s important: Small steps in the right direction compound over time. The difference between doing nothing, too much or just enough to move the needle could be the difference between you achieving a goal or not. Smart investors don’t ask for 75% return on their pound a year; they ask for 10% over 40 years.

17. Negative Visualisation

Practised by the Stoics (premeditatio malorum) is the concept of imagining worst-case scenarios to develop appreciation and prepare for contingencies. Focusing on things which you wish would never happen might appear to be a sadistic exercise, but if done correctly (leaving you upset, anxious or terrified,) leaves you with a fresh perspective for that thing.

I encourage you to think deeply and imagine losing somebody you love more than anything in the world. Somebody that if they passed, you’re life would be hollow. Imagine their funeral, how they would look in the casket, cold, and be sad that you never got a chance to say goodbye to them and that you’ll never get the chance to tell them what they meant to you. You’re surrounded by your friends and family at the service, who tell you how sorry they all are for your loss, but there’s never be anyone in that room who can imagine the pain that’s hurtling through your body.

Why it’s important: We take things for granted. Every. Single. One of us, and it’s often only when life pulls the rug right from under our feet that we realise it. This brutal exercise offers you a fresh opportunity to appreciate everything life has to offer you before it all gets taken away for good.

Sorry, if you cried by the way!

“When you look at all the people out in front of you, think of all the ones behind you”

- Seneca

18. OODA Loop

A four-step cyclic model for decision-making under pressure: Observe (gather information), Orient (analyse and understand the situation), Decide (choose your course of action), and Act (implement your decision, creating a feedback system for continuous improvement.

Developed by military strategist John Boyd, the OODA Loop recognises that situations change rapidly and that continuous adaptation beats perfect planning. I’ve just watched a documentary on the hunt for Osama Bin Laden, and when Seal Team 6 planned their operation, they went through rehearsals hundreds of times, planning for every type of situation. What they didn’t plan for was for one of the helicopters to crash outside the compound. After they gathered themselves, they tried to breach the compound using explosives to blow the door off, but the door was a false door. The team continuously adapted to their surroundings to complete their mission, and of course, the rest is history.

Why it’s important: This framework goes far beyond a military context and can be adapted to business, sports, personal conflicts or just about any competitive situation. The OODA Loop prevents you from staying stuck in outdated plans, with success often going to those who are readily adaptable and agile.

19. Opportunity Cost

Opportunity cost acknowledges that every choice you make means forgoing alternatives, making you more deliberate about how you allocate your time, energy, and resources.

If you decide to invest £5000 in a stock, the opportunity cost is everything else you forgo to make that investment. Maybe it’s a family holiday, home improvements or a rainy day pot.

Why it's important: Similar to inversion, opportunity costs asks us to think of the opportunities we could potentially miss out on as opposed to our traditional way of thinking, which is to think of the thing we want. It forces you to think of the whole picture in that given moment by considering alternatives. There is no such thing as a free lunch—everything has tradeoffs.

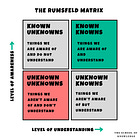

20. The Rumsfeld Matrix

Developed by former defence secretary Donald Rumsfeld, the Rumsfeld Matrix splits knowledge into four types: known knowns (things you know you know,) known unknowns (things you know you don’t know,) unknown knowns (things you don’t know you know) and unknown unknowns (things you don’t know you don’t know).

Aside from being a tongue twister, this framework is excellent for clarifying your current understanding of a topic or situation. It forces deliberate thinking, planning and risk management.

When the Americans were in Fallujah, Iraq, they were doing house-to-house fighting, and no other example exemplifies this matrix more so. Your known knowns are that you know you’re trained well and that somewhere in this city are people who want to kill you. Your known unknowns are that you don’t know how many, if they are male or female, what they’re wearing or how trained they are. Your unknown knowns are all the training and exercises you’ve forgotten about, but will come rushing back when you boot that door down and clear the room. The unknown unknowns are the things you don’t know you don’t know such as the booby trap you’ve just set off or the end of an AK47 that’s pointed right at the door ready to empty a magazine into your chest.

Why it’s important: The matrix helps you identify blind spots in your thinking and planning. If I were clearing that room, two grenades would be going in before me but even then there’s still a risk that there’s something I haven’t thought about. Not everything in life is life and death, but by acknowledging that there are things that can be planned for and things that can’t, you can build in buffers or think of ways to either mitigate or remove the risk. The Ukrainians have certainly learnt from the perils of house-to-house combat by using drone warfare—almost certainly an unknown unknown for how effective the Ukrainians will be at using them against the Russians when they crossed the Ukrainian border.

Interested in more? Check out my deep dive below:

21. Champion Bias

For every boxing champion we celebrate, thousands of others failed. Champion Bias occurs when we overestimate the likelihood of success by focusing only on the winners and ignoring all the failures. Mark Zuckerberg, a college dropout turned billionaire bro, created Facebook—the first social media platform that’s transformed how we interact online and in life. But, how many college dropouts does it take before you get a Mark Zuckerberg? How many college dropouts tried to start a tech company and failed, and how many just amounted to nothing or ordinary lives?

Where are their stories?

We all love success stories, especially rags-to-riches. Our screens are filled with the triumphs of champions, and we become their cheerleaders. Champion stories sell cinema tickets, books and sponsorship deals, not Steve the college dropout turned car mechanic.

Why it's important: Champion bias severely distorts our understanding of risk and probability. We naturally hear more stories about winners because they're inspiring and newsworthy, while failures remain invisible or forgotten. There’s nothing wrong with dreaming or shooting for the stars, but by focusing solely on the winners, you are choosing to have incomplete information from all the failures that people made before them. A smart strategy would be to seek out both.

Interested in more? Check out my deep dive below:

Until next time, Karl (The School of Knowledge).

Whenever you’re ready

The School of Knowledge helps you understand the world through practitioners. Those who try, fail and do (skin in the game). 📚💡

Join our growing community of like-minded lifelong learners here:

Great summary! Thanks!

it’s really great. It took me around 2 hours to read , analyze and note key points ! worth reading 🙏🏽