Navigating the Capital Cycle: Working Templates for Long-Term Investors and Business Owners

Understanding the behavioural traps that lead to booms and busts

Hey paid member, I want your advice on how to make this newsletter even better in 2026. Head over to the members only private chat and have your say by clicking HERE.

You can predict with near-certainty that an industry with 25% returns on capital today will earn far less in five years. You can also predict with near-certainty that an industry earning 5% returns today will improve. You cannot predict which specific companies will succeed or fail, when exactly the turn will come, or how management will respond. This distinction—between what’s predictable and what isn’t—is the essence of the Capital Cycle Framework, and it changes everything about how you should invest and run a business.

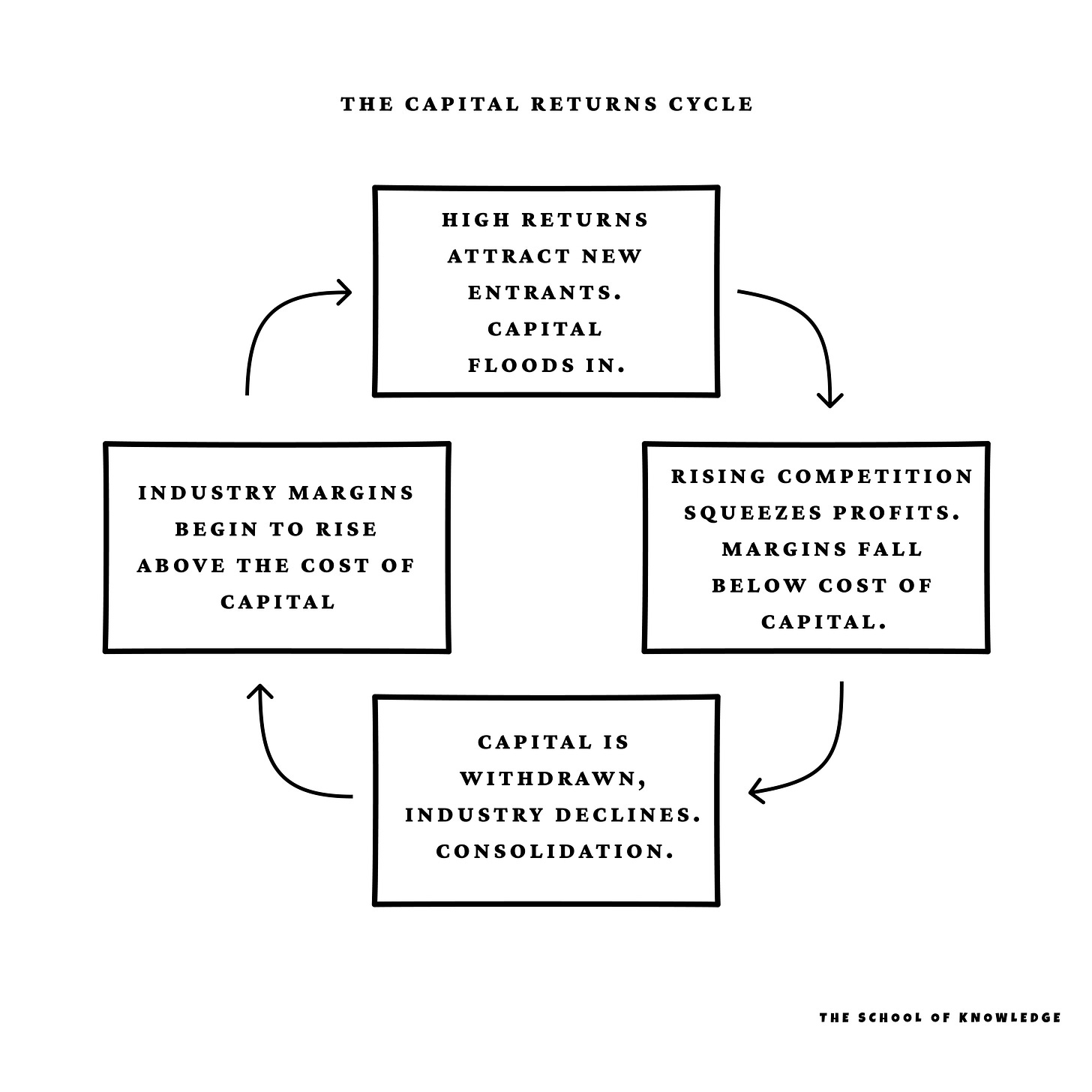

The Ebb and Flow of Capital

Companies that generate high returns tend to attract capital (think AI at the minute), whereas companies that generate low returns repel it. This simple statement is the core idea behind the Capital Cycle Framework, coined by Marathon Asset Management.1 Not only is this sequence of events predictable—it can also be capitalised on by the contrarian investor and business owner.

When companies start to make above-average returns, capital floods in. Banks, VCs and hedge funds want this train to continue past its designated stop and offer to fund the companies through debt or equity. The companies use this injection of capital to invest in growing their market dominance.

But what goes up must come down, and growing profits don’t just attract greedy investors—they attract competition. More players want to join the game and get their sliver of pie. When a company, industry or sector has had excess capital pumped into it and competition is fierce, it begins to develop overcapacity, margins start to get squeezed and profits start to decline.

When the cost of capital exceeds returns, worried investors start to panic and begin selling off their shares. Once this starts, and nothing interrupts it, it snowballs. They take their money and begin to look (and promote) the next best thing.2

But what happens when excess capital has left? The industry should start to consolidate as the debt-laden companies merge or get bought out. Once this has happened, and excess capital has moved over to the next best shiny thing, profits should start to climb up again and the cycle starts afresh.

The framework is laid out in Capital Returns, and the book’s editor, Edward Chancellor, argues that this ebb and flow of profits, capital and competition helps contribute to market bubbles and busts. Once you realise this, you can’t unsee it.

But if this is so obvious and so predictable, why does it continue to happen? The answer lies in how we think—or fail to think—when money is involved.

Let me introduce you to the behavioural traps.

Understanding Mean Reversion’s Role in the Capital Cycle

Capital cycle analysis is fundamentally about mean reversion—the idea that extreme things tend to move back towards average over time.

Understanding this should help investors not overreact when companies make above-average returns. Except it often doesn’t. People buy stocks they’ve never heard of based on a viral tweet. Businesses invest in building up their capacity at exactly the worst time—when everybody else has the same information and idea.

The Capital Cycle Framework shows that people spend too much time focusing on the supply side of the equation, and not the more predictable side—demand. Often in business, there are winner-take-all, or winners-take-most scenarios at play, so when something comes along that brings higher than normal profitability, the rest of the companies in the industry adopt what brought them the returns, or else they get left behind.

Demand for construction projects doesn’t triple overnight just because three new firms opened. But supply—the number of firms bidding—can double in 18 months when returns look attractive. You can’t predict which firms will win, but you can predict the overcapacity will crater margins.

So what do you do if you find yourself in an industry that’s either overhyped or bottomed out? Well, correct capital allocation principles still apply. And that starts with working out what return you expect to get from your investment (your internal rate of return, or IRR). If the investment falls below your desired rate of return, you should pass. If you remember back to my post on the Outsiders, Bill Anders did this. He sold the companies where General Dynamics wasn’t the number 1 or 2 player.

Divesting made financial sense.

So why don’t more people make decisions that are best for their situation? How do they consistently get burned by bad investments and poor capital allocation decisions for their business?

The answer has something to do with how you view your circumstances.

The Inside vs Outside View

The Inside vs. Outside View is about how you make predictions and judgements. The inside view focuses on the unique details of your specific situation—your plan, resources and circumstances. The outside view looks at what typically happens in similar situations by using statistical data and historical patterns from comparable cases.

Reading case studies is the easiest and cheapest way to learn about the Capital Cycle Framework.

Wall Street investors and the banks don’t care about the long-term prospects of a company, sector or industry, because they understand one simple fact: a dollar today is worth more to them than a dollar in the future, and Wall Street continues to play a blinder. We think that they’re the idiots with their short-sightedness, but they’re the ones who know that there’ll always be start-ups, IPOs and new fads that need funding. Even better, when the bubbles burst they offer their helping hand through debt.

Much like the prostitute who doesn’t care if the man who wants to pay her for sex has had a bath this week—Wall Street will continue to get into bed with anybody willing to pay them fees.

How to Avoid the Inside View

The inside view makes you overly optimistic because you focus on what makes your situation special whilst ignoring base rates. Most people naturally default to the inside view (”our project is different”), which is why projects run over budget and start-ups fail at predictable rates (90%). Using the outside view helps you make more accurate predictions by grounding your estimates in reality rather than hope. And no, prayers don’t help.

So how do you become somebody that takes the outside view? You study. You study because you don’t have the luxury of making the mistakes that the companies and investors make in real booms and busts. Not many companies survive being blown up. When you take the outside view, you’re opting to be a rational, contrarian, and independent thinker. They say: “it’s different this time,” but you ask: “why is it?”

It’s great if you can ride the 30ft wave and safely stay on board all the way back down to the applause of others, but if you can’t surf, or worse, swim—don’t bother getting in the water.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

The prisoner’s dilemma is a situation where two people can either cooperate with each other or betray each other, and the best outcome for both happens when they cooperate—but each person is also tempted to betray because it could give them an even better individual result.

The classic example: two prisoners are questioned separately. If both stay silent (cooperate), they each get 1 year in jail. If both betray each other, they each get 3 years. But if one betrays whilst the other stays silent, the betrayer goes free whilst the silent one gets 5 years.

Here’s how it plays out: Industry returns hit 25%. Company A invests in expansion. Company B sees this and thinks if I don’t match them, I’ll lose market share. Company C sees both expanding and thinks I can’t be the only one sitting still. Within 18 months, the industry has overcapacity, margins compress, and everyone’s worse off than if they’d all shown restraint.

How to Know if You’re in a Prisoner’s Dilemma

You’re in it when your main justification for investing is “everyone else is doing it” rather than your specific competitive advantage. If industry returns are above historical average and you feel pressure to invest or be left behind, the trap is already sprung.

You have four options:

Don’t play (if you’re strong). If you have a healthy balance sheet, sit out the expansion phase. Let competitors overcapitalise, wait for consolidation, then acquire the weak players.

Play defensively (if you’re medium). Match investments but use operating leverage, not debt. Maintain flexibility so you’re not locked into high fixed costs when margins compress.

Change the game (if you’re smart). Compete on specialisation, relationships, or quality instead of capacity and price. Find a niche where you’re not playing the same game.

Exit (if you’re realistic). Weakly positioned? Sell while returns are high and buyers are optimistic. Ego prevents most people from taking this option, but it’s often the right one.

Capital allocation rules:

Never take on significant debt to fund expansion when the entire industry is expanding

Build cash reserves when returns are high, not when they’re low

Question any investment justified primarily by “competitive defence”

Prioritise balance sheet strength over market share during booms—underperforming temporarily is fine if you survive to consolidate later

The brutal truth is most companies can’t escape because they’re not strong enough to sit it out and not smart enough to change the game. If that’s you, recognise it early and exit before the defection phase destroys your equity value.

Competition Neglect

Competition neglect is when people, or businesses, underestimate just how many others are thinking the same way they are, leading them to ignore how much competition they might face. This is exacerbated when the barrier to entry is low.

Social media companies don’t care if the viral piece of content was from an account with 40 or 400,000 followers, and neither do advertisers care about who’s willing to pay them the highest bid. Amazon has even made this an essential part of their business model with their Pay Per Click (PPC) advertising. A haunting example of competition neglect I’ve fallen victim to.

How to Avoid Competition Neglect

Remembering this mental model helps explain why people enter overly crowded markets, apply for long-shot opportunities without backup plans, and overestimate their chances in competitive situations. Recognising this helps you make more realistic plans by remembering: if something looks like a great opportunity to you, it probably looks that way to many others too.

Before entering a market or making a major investment, ask: What can we do that competitors can’t easily replicate? If your advantages are all things others could copy in 12 months—better marketing, more capital, harder work—you’re underestimating competition. Real advantages are structural: proprietary relationships, regulatory moats, network effects, or genuine technical superiority. If you don’t have one, reconsider the investment or business model.

Creative Destruction

The great reset.

Creative destruction is when new innovations destroy old industries and jobs whilst creating new, better ones to replace them. Netflix destroyed Blockbuster, but created new jobs in streaming technology and content production. Cars destroyed the horse-and-buggy industry, but created the massive automobile industry. EVs are now creating more change, not just in the cars we drive, but in the infrastructure we build around them.

Too much of a good thing doesn’t last forever, and disruptive technology arrives when you least expect it. You can’t avoid it, but you can learn to live with it.

How to Survive Creative Destruction

Step inside the mind of your competitors or a new, hungry and ambitious founder. How would they take your market share? Play devil’s advocate and ask yourself questions such as:

What emerging technology could make our core offering obsolete in 5 years?

Which competitor is operating on a completely different cost structure?

If I was building the business today, would I build it the same way?

When the landscape changes, you want to be on the necessary, not painful, side. Old jobs disappear, which hurts people in those industries, but new opportunities emerge that often make society better off overall. Understanding this helps you adapt to change rather than resist inevitable progress.

Now What? A Diagnostic Framework for Your Business

Understanding the behavioural traps of the capital cycle is one thing. Knowing where you are in it and what to do about it is another entirely.

Most business owners and investors can recognise a boom when they’re in one—but only in hindsight, and if you’re like me you fucking HATE hindsight. The challenge is identifying your position in real-time and making decisions that protect capital when everyone around you is expanding.

Below is a comprehensive diagnostic framework designed to answer three questions:

Where is your industry in the capital cycle?

How strong is your competitive position?

What should you do about it?

The framework consists of five interconnected tools for both business owners and investors:

1. Industry Position Assessment: A 12-question diagnostic that scores where your industry sits in the cycle (Trough, Downturn, Growth, or Peak). Uses observable market signals rather than guesswork.

2. Competitive Strength Assessment: A 5-question scorecard that evaluates whether you’re strong, medium, or weak relative to competitors. Your cycle position matters less if you’re positioned to survive.

3. Red Flag Checklist: 23 behavioural warning signs that you’re making capital cycle mistakes in real-time. The circuit-breaker when you’re caught up in momentum.

4. Balance Sheet Strength Scorecard: A detailed financial health assessment. Tells you whether you can survive a downturn, acquire competitors, or need to exit.

5. Quarterly Tracking Template: Track your scores over time to spot inflection points early. The cycle doesn’t announce itself—you have to watch for the signals.

These aren’t theoretical frameworks. They’re operational tools tested against real historical bubbles. When we scored the 2006 US housing bubble using the Red Flag Checklist, 22 out of 23 warning signs were present at the peak—validating that the thresholds work.

For each of the tools there is also a business owner and investor version.

Not ready to upgrade yet? Fair enough. But here’s what separates this from other business newsletters: it’s written by an operator for operators—people who need to make actual decisions on Monday morning.

The models, concepts and frameworks are free. The tools that let you use them aren’t.